Disc 1

That's The Way...

One More Time

Anticipation

Legend In Your Own Time

Julie Through The Glass

You're So Vain

We Have No Secrets

The Right Thing To Do

Mockingbird - (with James Taylor)

Haven't Got Time For The Pain

Older Sister

Waterfall

Attitude Dancing

In Times When My Head

Nobody Does It Better

You Belong To Me

Devoted To You - (with James Taylor)

Boys In The Trees

Vengeance

Come Upstairs

Jesse

Disc 2

Not A Day Goes By

Why

It Happens Everyday

Orpheus

Come Back Home

Coming Around Again

Give Me All Night

The Stuff That Dreams Are Made Of

All I Want Is You

Let The River Run

My Romance

Better Not Tell Her

Love Of My Life

Like A River

Two Little Sisters

Film Noir

Scar

Actress

Touched By The Sun - (Live 1995)

Credits

This Compilation Produced for Release by: Carly Simon, David McLees & Gary Peterson

Remastering: Bill Inglot & Dan Hersch

Product Manager: Jimmy Edwards

Liner Notes Coordinator: Tim Scanlin

Editorial Supervisor: Sheryl Farber

Business Affairs: Maila Doss & Steve Poltorak

Art Direction & Design: Hugh Brown & Julie Vlasak

Personal Management: Arlyne Rothberg

Legal Representation: L. Lee Phillips

Liners

We were at a booth in the Middlesex Diner, Margaret and I. North Brunswick, New Jersey. It was 1975, we were teens, and I was cool because Margaret was with me. And Margaret was almost intolerably cool. I gestured to the waitress for a fresh round of Cokes like a very rich man placing a bid at Sotheby's--an upraised forefinger, a swirl. Oh, I bet you wish you were that cool. (Don't you, don't you, don't you, now?)

Then Margaret's eyes flared into twin klieg lamps of hazel. She clamped her hand on my forearm. There is an urgency in the grasp of beautiful teen girls transmitted through no other hands.

"Jack. Jack. Have you seen Carly's new album?"

I had not. But I had a brand-new and still sticky coolness to hang on to, so I pretended I had.

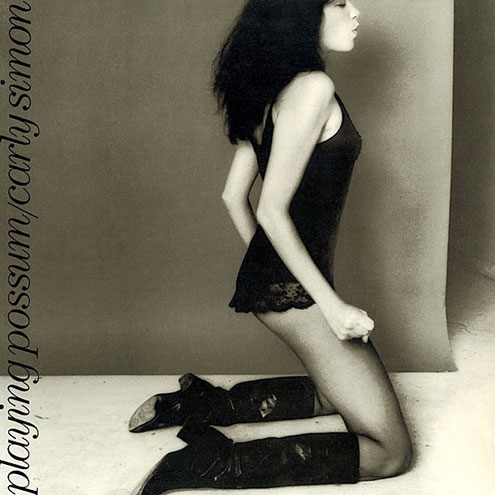

In short order, of course, I got the album, Playing Possum, with the shocking cover of a stockinged Carly Simon, kneeling, fists clenched, sexy and defiant. Nineteen seventy-five. Now, we all know how in later years a Miss Madonna Ciccone drew a horrified gasp from the planet for pushing the envelope of erotic marketing--sounds like an excessive squeezing of tomatoes at the grocery, no?--into shapes no balloon-twisting act ever dreamed of. Yet there was Carly Simon, in 1975, igniting civil wars in what we then still called Women's Lib. I began to feel old when Madonna began to strip.

Be that as it may. Playing Possum became the background music of that muggy summer for me. Before it, I don't think I knew exactly who Carly Simon was. A big pop star, yes. A striking woman with spidery limbs, two yards of smile, and the voice of at least three strong singers. Of course. But I had lived an uncool youth and knew little of the popular world. By my third spinning of Possum, I asked God to keep her by me, tidily accessible in vinyl, forever.

The most implacable adolescent resolution is usually good for about 12 hours. Lucky for the teen, lucky for us all, some vows are made six or seven decks below our most fierce and flimsy determinations. They aren't choices at all.

So I unsystematically found and bought Carly's other albums, as muggy turned to crisp that year and I began to shave every single day. Poor CD generation: I lament for you as my generation's forebears pitied us for missing out on the gas-guzzlers they themselves enjoyed. You can't know how picking up a new album felt. There was something aristocratic in it, as though we were rifling through, plucking out, and peering at hundreds of slim canvas portraits. Size makes a difference, no matter how owners of tiny little CDs protest.

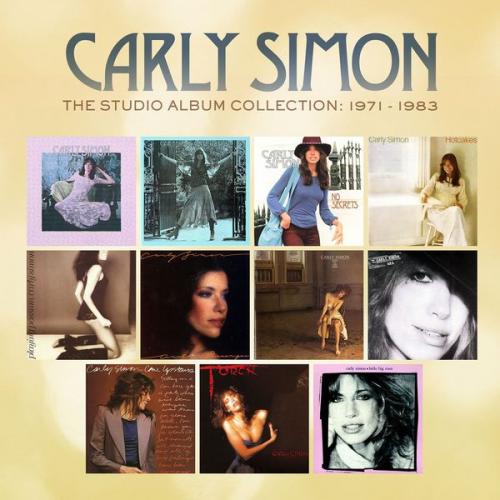

I shopped. There was the green album, Anticipation. On it Carly is a hip Amazon warrior in a flowery skirt, guarding the entry to a lush park as though she herself, hands gripping the posts on either side, were the provocative gate. I then remembered the title song. Of course. It was a shade on the folk side for me; I had not loved it in its heyday. But that made her all the more interesting. I had, after all, just recently become acquainted with the alternately torrential and gentle cascades of Possum. Carly Simon, I surmised, was not exclusively a rocker, not necessarily a folk balladeer, and not limited to any one sphere at all.

I got the pink album, her first, next. Even the cover is raw. Carly sits on a divan of sorts looking as we do when a relative has lied to us about not taking any more damn pictures. And the album felt more like cardboard than albums usually did. There was no gloss. What was there, was her first hit, "That's The Way I've Always Heard It Should Be," cowritten with Carly's most steadfast--and virtually only--collaborator, Jake Brackman. Apparently they have remained great friends for many years, which may account for a wedding of lyrics to music as harmoniously deft as what Carly has customarily provided all by herself. I dare say that when brighter creatures conquer and then catalog every little thing about us, this song will be filed away in a high-tech alien cabinet as the most glorious example of an unknown singer-songwriter's advent into the realm of the very known.

I was now a (shaving) boy with a purpose in the record palaces, circumventing life-size displays of Fleetwood Mac and cardboard cutouts of The Eagles with the surefootedness of a skilled square dancer. The Fleetwood Mac wasn't easy, either, what with the extra width of a Stevie Nicks cape to bypass. But I did what I had to do. In no time at all I had adopted the adroit trademark of the Carly Simon seeker at the record stores: namely, the Paul Simons got a fast sneer and a faster shuffle into the Santana slot. I am not proud of this. I noticed too that my voice nearly boomed on those occasions when I had to ask for her music at the counter. A reflex of pride, methinks, a variation of a mother bellowing to the friend sitting ten inches away from her that her son's a doctor. But Carly listeners understand.

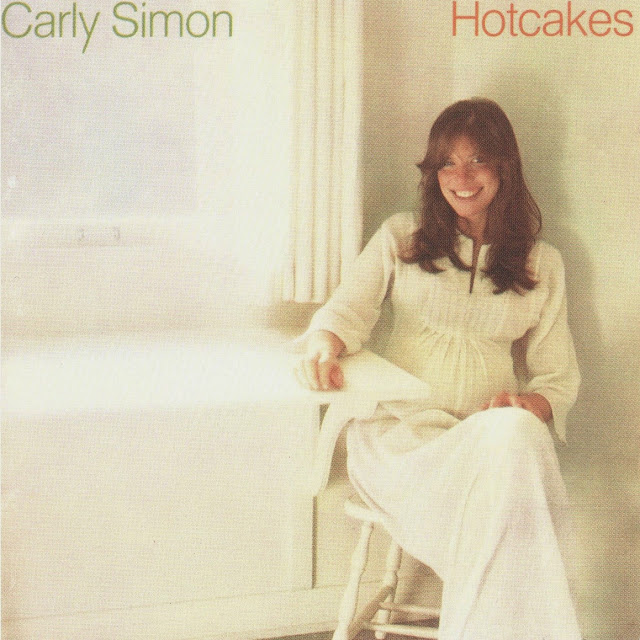

Hotcakes joined my collection, more mysterious in cover than even Playing Possum. Why, there's Carly in a sea of whiteness--a Martha Stewart opium dream of a country house guestroom comes to mind--looking awfully coy and exceedingly with child. One reads the song list and sees a cut titled "Think I'm Gonna Have a Baby." Yet the album is named after a jazzy little closer on the first side. This is deliberate ambiguity of no small order. It's also witty, in a devilish and unpretentious way.

That year of discovery I saved No Secrets for last. I was least interested in what the entire world embraced. By 1975 "You're So Vain" had been in the nation's bloodstream for years like a spiked vitamin boost. My brother's girlfriend adored it because it reached #1 on the day she bought her first car. I thought then, as I think now, that there could be no better hit with which to christen the ownership of a vehicle. "You're So Vain" introduced gavotte to those unfamiliar with the score of My Fair Lady, and it was responsible for a zillion rhetorical "don't you, don't you, don't you's?" ascending, mostly off-key and often drunkenly, into the nonvain heavens. No Secrets could wait, certainly till the mother-of-pearl Hotcakes was fully ingested.

I now had my Elektra Carly, all the songs of her first fame, the work done while the ink of her stardom was still tacky to the touch. All of them I played until I knew every song by heart. All of them I played while pacing the floor, impatient for the artistry I knew, absolutely knew, was coming.

I should by rights be able to say that Carly's ingénue period is marked by a discernable naïveté of lyric, an overindulgence in musical composition, and an all-around less sophisticated and more enthusiastic hand than her later work. I certainly tried. I have in fact just gone through five cigarettes and a full pot of coffee while thinking about how to define the differences between the early, Elektra Carly and the more mature Warner, Epic, and Arista artist. This is what I've come up with: Her voice is fractionally more youthful in her younger days. And mine is five cigarettes closer to a rasp.

Yes, one can hear vibrations of a '60s hippie ethos in the first few albums. Naturally. These works were written when the residue of unwashed belief was still lingering in the air, before the incipient self-adoration we were all about to caress in the '70s and make violent love to in the '80s was envisioned. And these songs were produced without the flamboyant bells and sleek whistles available in later years. Studios then, from the pictures I've seen, looked more like friendly caverns for musical folk and less like operating theaters for laser therapy.

But we're here about the songs themselves and only the songs, most of which were written completely by Miss Simon. With these twin understandings in place, traditional evaluations of skill based upon the influences of the calendar don't apply. The Warner and Arista Carly Simon may exhibit a shade more polish than the girl on Elektra, but I'm not even sure of that. Her gift did not grow into itself. It was always there and always explored fully.

I call "One More Time," from Album One, Carly Simon, to the stand. It sounds like Carly ran up to an open mic by the Pottery Barn in the mall, and an accomplice threw a big ole tarp over her for several minutes. It's that basic in production. But the song and the singer emerge whole, and thunderously so. Played today, over 30 years later, it holds up just fine. Having been spun from real emotion and thought, "One More Time" survives intact, while other songs of the period, dependent on that year's mode of mind-set, deflate. It slides, it growls, it's cutesy, and it's pissed-off. It's a one-act play staged in a smoky barn. It's such, such fun, people!

Another memory: I was the slightly chubby boy walking down the stairs. Ten, eleven years old? My brother's back was just ahead. I sang, "Then you turn on the ra-di-o, and sing with the singer in the band . . ." My brother swung around and said, "You like Carly Simon?" I was, as has been noted, not with it. I was unsure if "Carly Simon" was a person or a thing, a style. "I sure like that song," I said. Then I sang more of it. Maybe the wry scolding in that deceptively sophisticated tune lost a little of its cynical power as voiced by a chunky boy in chunkier eyeglasses. No matter. My brother, mercifully, ignored me. Outside, I lisped "Legend In Your Own Time" all over again. It seemed unlike other pop songs because the words and the music belonged absolutely to each other. It was edgy and finely crafted, with much subtext; one understands obliquely the just barely suppressed ache of its narrator, and she never once refers to having been misled by Mr. Legend herself. All this I knew in my chunky soul. I might even have spoken as much, if pressed further. I would have vehemently pointed out how well-crafted the song was, and all that thubtext.

We have our sweet suspicions about the songwriters whose work we come to know well. Take "Julie Through The Glass." This is a tender prayer for a niece; the infant Julie was the daughter of Carly's sister Lucy. That is fact, not supposition. But I think Carly herself cherishes this song very deeply indeed, more so than most of her other less famous tunes. Just as I have always felt that writing the weightless and dreamy "Mind On My Man"--not within this anthology; you must toss aside Paul Simons and get yourself a whole Hotcakes--was a seamless experience for her. That is, for lack of more precise phrasing, just how it feels.

"The Right Thing To Do," "We Have No Secrets," "You're So Vain" (sound bite ahead): a trio with more bullets in it than a threesome of bad guys at the end of a Western. When my generation fell in love, we skipped along to "The Right Thing To Do." The song pops its vest buttons crowing about love and, impossibly, we don't want to slap its face; it's too good, too endearing. When our love took on complex shadows, we stopped skipping and mused to "We Have No Secrets." The best thing I can say about that song is that it not only puts you on the beach with the rum-chugging slut, but it also returns you to the living room and behind the narrowed, introspective eyes of the singer. (That is, let me tell you, what anyone who ever put pen to paper dreams of.) And when a few of our loves made it big and left Gucci-heel imprints on our backs, we turned to the vitriolic glee of "You're So Vain" (or, as the vocally supportive Mick Jagger [Sir Mick Jagger--sorry] has it, "You're So Vine"). I ask you: Had a girl singer-songwriter ever attacked before? And, if one had, did she manage to infuse the bitterness with palpable sorrow and make you snap your fingers and shake your shoulders to it too?

Hotcakes. Hmm. In a large sense, men go to war to fight for the pregnant women at home. I rather think, though, that there's a horse that has forever been staring at the cart's ass; men scurry off so because a bayonet is easier to fathom, and in some ways preferable to deal with, than an expectant mother. We don't get it, and we're afraid of it. Thus do I approach Hotcakes in khaki and with fake twigs sticking out of my helmet. Carly was about two hours away from giving birth to her daughter, Sally, when this was recorded. Or so it looks to me, a dumb guy. As a dumb guy, I hear the wonderful songs on it and automatically think, Ah, yes, the glow of motherhood is clearly responsible for the unalloyed joy of "Haven't Got Time For The Pain," the spunky kick of "Mockingbird," the retro-fun diary entry of "Older Sister."

No good. I am a private with no future in the intelligence branches of the militia. Because "Waterfall," from Playing Possum, is as brimming with primal elation as "Haven't Got Time For The Pain"; "All I Want Is You," from Coming Around Again, owes nothing in romantic corroboration to "Mockingbird"; and "Come Upstairs," from Come Upstairs, does for a wandering beau exactly what "Older Sister" does for . . . well, an older sister. It presents, thrillingly, a layer of awe under a veneer of irritation. Expecting or free to drink caffeine, single or married, in her twenties or in her forties, Carly Simon can't not do justice to what is going on in her heart and in her life. In the process, in her exploring of the undercurrents eddying below the ordinary and extraordinary times of her life, she can't not identify what is circling around us as well.

A word about the life, if I may. Carly Simon is the third daughter of Richard and Andrea Simon. Richard Simon cofounded the Simon & Schuster publishing firm. From this somewhat prosaic fact have unfolded over the years approximately 8,000 stories--some of them written by real, honest-to-God reporters too--in which she is referred to in one form or another as a madcap heiress. Indeed.

Carly Simon was married to singer-songwriter James Taylor for a number of years, and they had two children. Even before their champagne glasses clinked together, their union was probed by Le Media with sharper implements, more indefatigable gusto, more subjective and often scary guesswork, and less class than the Lindbergh baby kidnapping.

Now, I can't state that Carly doesn't have at least one feather boa in her closet. Nor would I presume that her life with James Taylor was an uninterrupted canoe ride of bliss on a gurgling stream. I can only say here what you already know: that the feathers, or lack thereof, or the canoe, or the feathers trailing wet on the outside of the canoe, have everything to do with who she is and what she creates as an artist and have absolutely nothing to do with us.

That is condescending. I hear it. Excuse me, pardon that, and know that the discipline I so strenuously endorse regarding the unimportance of her private life is one I have needed badly to practice myself. It's human nature, after all, if a marginally seedy aspect of it. We are touched by the work and subsequently feel that the artist belongs to us in some fashion. But it's only the work that does, because she gives it to us, and we would do well to roll up an old copy of Rolling Stone--one containing those fabulous paragraphs of soft-core porn they so commonly employed when seriously discussing female musicians--and whack ourselves on the thighs, chanting, "I will not sink that low, I will not sink that low...."

I have, in any event.

But we are human, you and I, no matter how I sermonize. So I will offer up two juicy bones: Carly got married again (get the children out of the room, please) to Jim Hart, the affable, erudite editor of Boston's DoubleTake magazine. And in Carly's own home--this is on very good authority--there is a small flight of stairs leading absolutely nowhere.

Wild stuff, huh? But what else would you expect of a madcap ex-wife of James Taylor, anyway?

Back to de music. On second thought, let's go to the movies. Be warned. I am about to get very excited.

In 1986 another girl drew my attention to Carly. We were at work. Bonnie gave me a look that I can only describe as adversarial, if not downright nasty, and said, "Have you heard that song, 'Coming Around Again'? Did you know that that's Carly Simon?" She uttered the name as though informing me that my child had been seized for breaking into a store window.

Bonnie knew, as did everyone who knew me, that I cared enormously about Carly's songs. What she didn't know is that I never listened to the radio. I didn't know this new song. But old habits die hard, and I replied with the lie I had used with Margaret years before. Of course I knew it. Moreover, I lied as if my child had in fact been breaking into the store to save a burning, presumably younger and smaller kid.

To me, the essence of Carly's gift is most evident in the songs she has written for film. Which makes perfect artistic sense in her case. Great popular music writers usually don't have the facility to write well for a film; too often their talents are solely dependent on how incident, be it romantic or otherwise, is directly digested by them. I want Joe/Jane, Joe/Jane don't want me, or Joe/Jane is my sweetie, and I do believe I will pick up this guitar and sing about that. These songwriters strike responsive chords with their audiences because their audiences, in a very real sense, come to them, ready to be informed of just what heartbreak or rapture sounds like. Joe/Jane didn't want them either, or faked it really well once. This is pulled off often enough to launch a megahit.

But Carly Simon confronts life both intimately--as we all of course must--and from a few yards away as well. She has described her approach to songwriting as a necessarily tangential thing; she stands a little to the left of the experience even as she is immersed within it, and sees and records from that angle. If Joe is being peevish, she will lament the situation as it grieves her. But her vision is always more expansive. In--ahem--cinematic terms, she pans back and exposes her grief, yes, but she takes in Joe's folded arms and shaking head, too, and looks behind even that. That is how she creates her songs.

And this is in itself a mirror image of what happens to most of us at the movies. There are characters moving in a scenario, and we watch and take all of it in, allowing it to then touch us. In her songs, Carly herself provides both character and scope. She stars in the moments of her life yet sends an obliging shadow of herself to a decent mezzanine seat on the right. So, when given the chore of creating for someone else's fictive reality--a movie--she is already exquisitely equipped. Because she has an instinct for observing, honed from standing across, and well apart, from every lousy or loving Joe she ever knew.

Hear the first four strokes of the bow, the opening notes, of "Coming Around Again." They last for about a quarter of a second and are astounding. A door opens or a window slides up in them or a head is raised with a quick and tense breath while they play. In those notes, in that moment, the scene is set. You don't know just what it is, really, But it is unmistakably a revelation of some sort, and not altogether a joyous one.

The song commences: what Mommy does, what Daddy does. Baby's got the croup. Then the activities described take an unsettling turn: window glass shatters, and what you know was a perfectly good soufflé is cremated. Yet it is still, all of it, a straightforward and lyrical list. And this ties into the other thing Carly creates with extravagant beauty--fable, lullaby. The bare bones of a circumstance are laid out, the music is haunting and lovely, and the two elements combine to make a sum too magnificent to be expected from any two parts.

Who is telling the story? The wife? Possibly. But then the wife, or maybe even the husband, clearly takes over in a desperately tenacious, first-person plea: "I know nothing stays the same/But if you're willing to play the game/It's coming around again." As far as this listener is concerned, that is the watch-cry of human relations. "Coming Around Again," even in its pain, celebrates the cycles of life as we live it with a loved one. It is as naturally satisfying as the feel of the pulse of that loved one. It's a heartbeat of domesticity.

It's too bad that I get all ponderous about what is essentially a wonderful song for you to enjoy. I am not always so leaden. Honest. A matter of days after Bonnie acquainted me with "Coming Around Again," I could be heard singing it lustily and longingly at work. Much. Then another colleague turned to me and said, in the nicest, softest manner, "Why do you keep singing that, when you can't sing?" My brother had been kinder, with "Legend." Or at least in a hurry.

The Oscar ® -winning "Let The River Run" is perhaps the best song written for a movie, ever. If Hollywood engaged in bribes to determine the names in the Academy envelopes--and I do not for a moment suppose such is the case--there was no cash greasy enough to slip in under its perfection. It was written for Working Girl, and I can't help but speculate on what the film's theme might have drawn forth from other songwriters. At least several would have undoubtedly been career-issue-specific. Some might have been bitter, with stinging electric guitars. Others, poetic yearnings from the title character's heart, set to a tinkling piano.

Carly Simon took her customary wide lens of viewing a scenario and got so far out she broke the zoom. She saw a story about a frustrated secretary's struggle for recognition and saw every aspirant who ever wanted something. Then she saw the glorious momentum beneath the frustrations, the blue in God's irises, rain forests and drums. She gave us a spectacular and feeling anthem; she turned subways into space shuttles.

I was elated when I learned that "Two Little Sisters (Theme From 'Marvin's Room')" was to be included in this anthology. The film was not a smash. Not nearly enough people heard this exquisite lullaby. After you do and lower your eyes to the devastating lilt of it, note the craft employed in the composition. Hear how the elder sister, the one with simpler expectations, voices them with just enough words to bounce on top of the cadence. Then listen to the younger sister's more frenetic desires, subtly underlined by the crowd of lyric used to express them. This is masterful songwriting. That Meryl Streep--kid sis in the movie, transcendent actress in life--supplies backup vocals enhances the gripping sadness of this fable-as-song. It breaks your heart. It shatters mine, every time.

Dates are deadly stuff. I employ few here and only one chart number. Faces, names, pieces of songs or whole ones, passages from favorite books: these I remember with almost supernatural clarity. But the month, the year? My memory refuses to retain such dry fodder; it is a huffy beast and takes issue with being cast as a bean counter. Besides, we have the Internet these days.

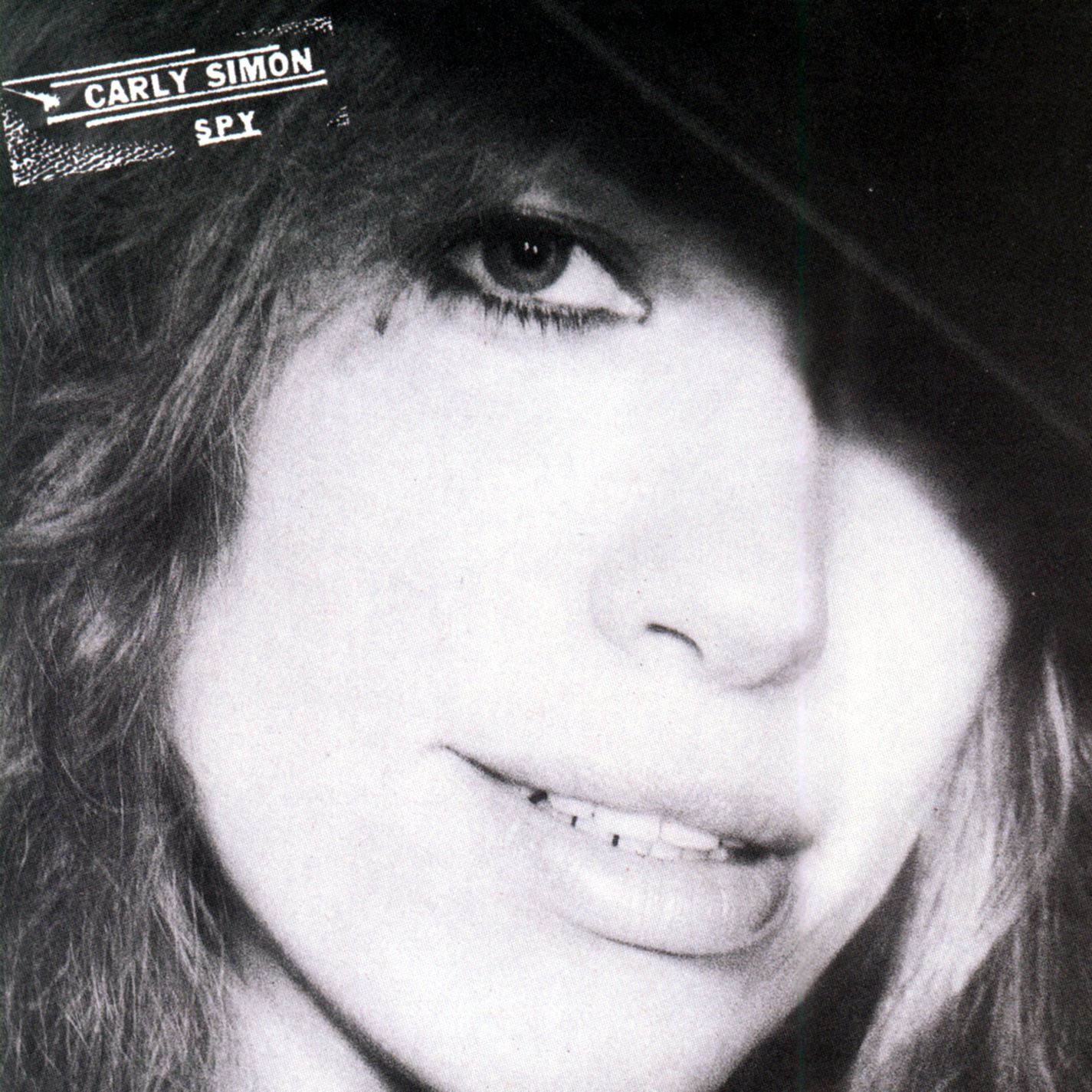

Carly Simon's Spy, with its four-minute opera of rocking jealousy, "Vengeance," closed the glass-brick doors to the '70s. We move to the '80s, the '90s. Mullets and greed. How did these times affect the Carly Simon not writing for the movies? Probably a good deal less substantially than a couple of weeks of replumbing the Carly Simon home bathrooms. As is logical. If bad haircuts and avarice reverberated in your own life, I'd be surprised if you could tell me how. All that endures, if anything of us is to last, is what we were actually doing.

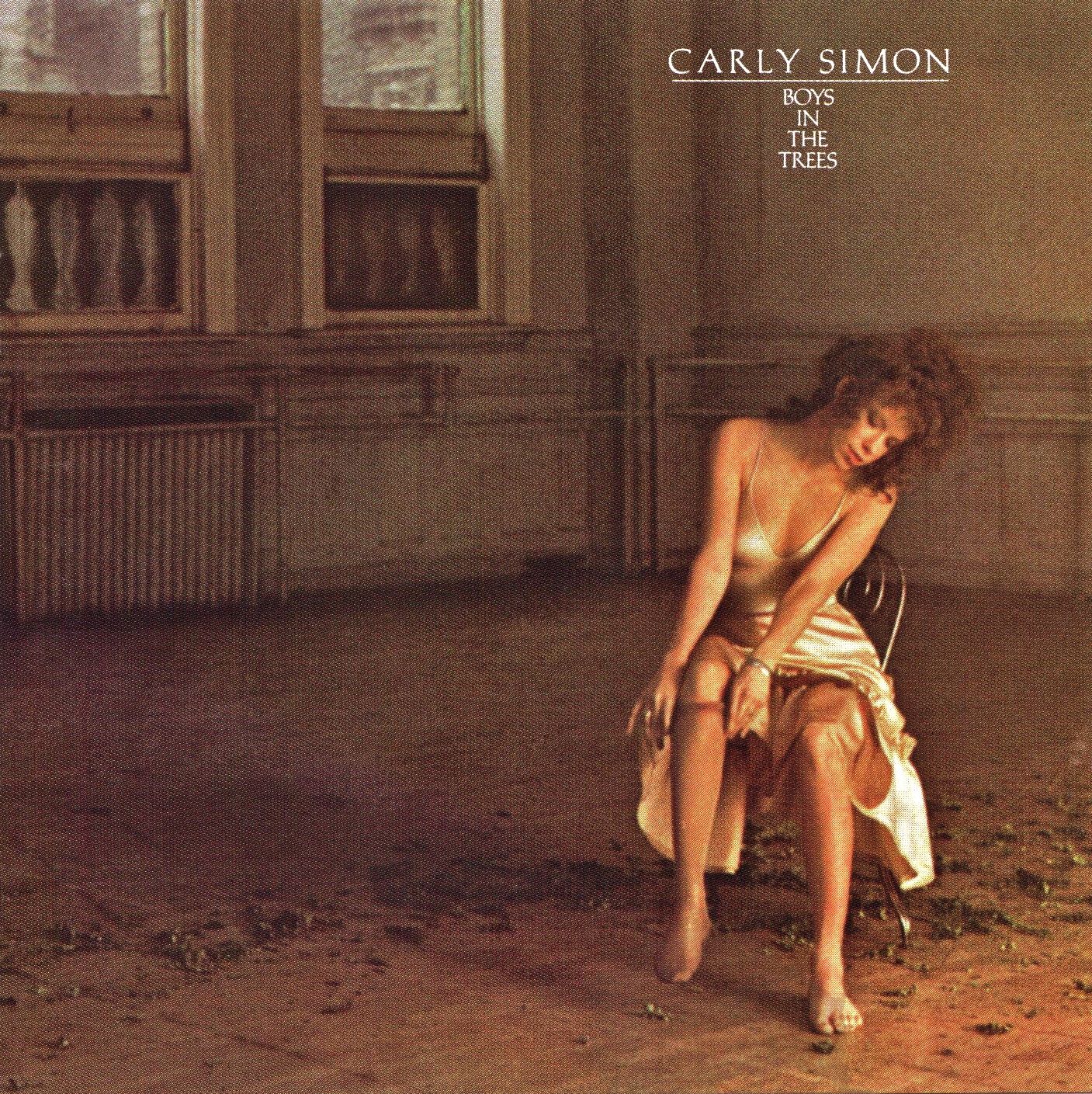

I was in Florida. I went to the dentist and heard on his receptionist's radio--not mine, you'll notice--a thrilling ad for Boys In The Trees. I drove to Peaches Records with a numb mouth and shaking hands. Carly doesn't ever apologize for emotional intensity, and the no-holds-barred covetousness of her "You Belong To Me" has not a whiff of the rejected angst of other versions. She is waving a contract in her lover's face so that he can better see his own, rotten, faithless signature upon it.

I lost my hair and returned to New Jersey. She recorded three albums of sensational standards, Torch, My Romance, and Film Noir. Before Torch, no artist of her stature had yet so mined the riches of the prewar and postwar music scene. Shortly thereafter, several big names with wonderful voices took the cue. "Not A Day Goes By," from Torch, is not a classic. But Carly recognized a beauty when she saw it and saw to it that this plaintive Sondheim gem was done its full justice by what I swear is a superhuman alto.

I moved back to Florida. (That's the law in New Jersey.) Carly Simon took Britain like Alfred the Great with an eerie and unshakable pop ditty called "Why." She wrote a lot of music and flipped a new spin on the Orpheus legend, as valid as Steely Dan's insightful twist on the Ulysses tale in "Home At Last." In Carly's "Orpheus"--as I hear it--Eurydice is a woman trying to make a man see what men rarely see. And the song's power works just as lucidly for those ignorant of Greco-Roman myth; Orpheus could be Fred. The guitar strumming alone speaks of emphatic regret better than any music and most words I've ever heard. A leggy spy in the house of Carly tells me it is the favorite song of its creator (creatoress?). The lady got taste.

I moved to Tennessee. Carly Simon was everywhere, doing everything.

Have You Seen Me Lately? was originally a film project. Some seductive bars of its music made it to Postcards From The Edge, and the remaining album itself has a distinctive wholeness, yet one not easily summarized. Possum is a shimmering work, wet throughout; Another Passenger (vinyl home of the aching self-awareness of "In Times When My Head") a lush catalog of stunningly realized passions; Come Upstairs an invitation to a very private party; and Spoiled Girl a whole lot of woman, an exciting documentary for those unfamiliar with the gender. Have You Seen Me Lately? is... a day in the life. And the sexy and not terribly guilt-ridden "Better Not Tell Her" is just one mood from that day. All the other moods and moments she captures are real, compelling, and lived through by the time most of us tuck ourselves in for the night.

I left Tennessee and started writing. Carly decided that a relatively impromptu concert set in the middle of New York's Grand Central Station would be an interesting thing to do. I dug up that old, rolled Rolling Stone and administered severe beatings to myself for having flown, instead of trained it, to Pittsburgh that day. But God be thanked for PBS and the swell job they did of recording the show. In the program, Carly Simon, the pop star with the notorious fear of performing, picks out the opening chords to "Touched By The Sun" as her band and backup singers shuffle onto the platform and, one by one, sling on their guitars or pick up their mics just in time to join in, on cue. It's rehearsed, of course. So were the most ostensibly spontaneous and joyful dances of Fred and Ginger.

I returned to Tennessee and tore up pages. She worked with Jimmy Webb on Film Noir and inspired an entire orchestra to record in retro hats and sinister sunglasses. The title song is a new and potent collaboration from the two (Simon and Webb--not shades and headwear), a lush and scenic homage to the genre they so smokily capture in every song recorded on the album.

My time grows short. Anthology: a rather forbidding word. Ignore it. It is as meaningless as a set of Billboard chart numbers. Look to the songs, and hear the proof of Carly Simon's constancy to her own gift, no matter the year. In 1994's Letters Never Sent she displays extraordinary talent in juxtaposing the wary with the heartfelt; she did the same thing in the debut album. The Bedroom Tapes, Carly's 2000 release, is a landscape colored with poignant perspective and spurts of fun; the seemingly fragile "Scar" moves dreamily from anguish to strength, while the slightly tipsy "Actress" splashes you a little with her drink and the glee of Carly's piercing humor. But so too does the classic No Secrets pause for interior moments, for precisely drawn depth, then toss its head, grab the car keys, and go out on the town. Anthology? Decades? It all may as well be one fantastic, if rather busy, year in her life. In all of it, too, from Carly then to Carly now, her wry humor winks at you like the pal you like a little better than your best friend.

I will leave you alone now. If, good reader, you have stayed with me thus far, you have my sincere thanks. You have as well my raised eyebrow. Maybe some writers are good enough to compete for time with listening to a Carly Simon collection. But they're mostly dead, and I don't think I'm one of them.

~ by Jack Mauro